Field Recordings, from Sounds of Crisis (2020)

Edith Jeřábková

If you say truth, suspicion is aroused at once. Truth and power have tormented and fascinated theologians, philosophers and lawgivers since time immemorial. In narratives they take the form of good and evil. We cannot even agree as to whether truth is a construct or an objective essence. For some time now we have been bombarded with the idea that we are living in a post-truth age. Such an era certainly has its champions, though on second thoughts let’s not go there. In the second half of the 20th century, the prefix "post-" was grafted onto a host of other concepts, thus becoming an integral part thereof. This means that, leaving aside ‘big themes’ such as the problematic of modern societies, their ideologies, culture, politics, etc., ‘post-like’ concepts are finding their way into lesser or greater intellectual or artistic currents of thought. The tendency to ‘glorify’ the prefix post-has resulted in that which we call postmodernism1.

This explains a second term used within the same context, namely the post-factual era. After all, there is a difference between truth and fact, and there is still a way to go before we arrive at an opinion. Truth is associated with time and is fixed within it, while a fact is a piece of information and as such is more associated with place. An opinion is a matter of interpretation and subordinate to the subject. The breakdown of truth into facts and opinions is caused by the fragmentation of knowledge and the thorny problem of the Cartesian subject, which was expertly set forth by Slavoj Žižek in the introduction A Spectre Is Haunting to his book The Ticklish Subject. Why do I mention this? Because inasmuch as Dan Walwin calls his exhibition True place, the terrain becomes even more complicated, especially when trying to translate the title – should we emphasise fact or truth? The fact leads us to reality, and in combination with the image we once again find ourselves in the old cycle of representation.

It almost seems as though Walwin is looking for a way out of recent strategies that attempted, in anti-essentialist style, to fill the gap between reality and image, and looking for the essentialist remnants of truth in various places where they might have been overlooked. It is not that he wants to persuade us of the truth, and certainly not his own. It is more that he is interested in realism, as it were, in representation. In what way and by what means are images and works realistic. To this end, he selects locations for his videos with a particular quality, places that appear abandoned by modern society and yet contain details that seek to lead us somewhere. This is a kind of deceptive forensic method of field research into the terrain of our society and civilisation that is not visible and leaves behind it only traces, places that were used “once”, strangely still, that we would like to leave to their slow pace. Perhaps it is this slow tempo that we would like to appropriate for ourselves. However, we should not fixate so much on the places themselves, even though we might speculate further as to whether these are urban wilds and non-places that age in specific ways, are generic and in which emotions take residence often linked with the concrete details referred to, sources of uncertain collective memories. It was perhaps the sheer range of these emotions that were the inspiration behind the title True place, which could equally well refer to a love story, development project, spiritual journey, or financial plan.

The pneumatic sound of a machine sounds like gunfire, a highway and silence. A melody enters the trickle of running water for a moment. Pressurised water spray and a highly modified aggressive technical sound resemble shooting. Bells in the distance and the sound of a bird, a loud hum and a deafening bell, a physical experience as though we were standing in the bell tower itself. Field recordings, sound detectors, ASMR, electronic experiments and similar trends in contemporary music demonstrate its interest in the search for sounds that would point to our relationship with reality, and that reality is a place from which we may once again proceed and draw down, above all for affective experience. In his videos Walwin treats sound similarly to image –but this does not mean illustratively. Sound is not always a field or audio recording and the same is true of the image. Walwin has no interest in some kind of edgy originality. Individual sounds wax and wane, appear and are lost, interrupt and materialise, intertwine and are sustained according to what the audio-visual composition needs to retain its “force field”.

Although the objects captured in the images and sounds possess their own qualities, it is primarily the film, object and somatic quality that maintain our interest with its compositional ingenuity, technological care and emotional range of videos and generic and precisely organised sculptural structures. Tension accumulates not only by means of the randomly moving sound, but also the intoxicated movement of the camera, and these jointly generate a dual sense of unease, alerting us to the uncertain atmosphere of the environment that we are observing from without and experiencing from within. In places it comes close to a hypnotic synergy. The image oscillates between viewer and artist, as though for a brief instant it ceases to be indexical. A viewer used to reading something in galleries is forced to think of the artist and asks him, at least in imagination, why and how. The viewer awaits an explanation in the image that never arrives, and yet she continues to wait, because the overall composition keeps her on standby.

Walwin created a similarly dramatic atmosphere in the gallery space itself by means of the exhibition architecture. He is interested in how video and sound operate, together, separately, and even deconstructed to their physical essence (light and darkness, silence and noise, and synaesthetically as dry and wet). We are interested in what period of the film we find ourselves, and yet this is not important. The bench that underscores the film-theatre presentation is placed by a wall in the corner in such a way that it does not offer a good angle from which to view the film (or rather video). It is more like a sculpture, especially if we look at it with backs to the projection, in which case a distinct environment is created in the corner of the room and we automatically switch the projector for an industrial camera. This is an environment that could appear in one of Walwin’s videos, though could also be a safe space where we are not being bombarded with visual inputs.

The sound accompanying the large video is powerful and dominates the entire gallery. The bells ring out through the gallery’s arches as though from a church, and sometimes they coincide with the bell belonging to the Church of St. Anthony of Padua on Strossmayer Square not far from the gallery. The bell escapes the deafening sound and in the image grows smaller and wanders through the landscape as though in search of a place, leading us like a storyteller or a guide in a documentary film. Video images alternate with construction sites, apartment blocks bristling with satellites and the urban wilds. Walwin includes in the video a small exhibition of photographs, which seem as though they would like to reveal something to the investigative eye of the viewer.

The thirdsite of intensity is the corner of the gallery, where the light of two monitors, one on top of the other on a metal truss, shines onto the wall. The viewer must lean against the wall in order to see the screens and follow the video. This installation appears as autonomous as the one in the far corner with the bench. The glow and shape of the monitors on the truss create the impression of technology. The close confrontation with the moving picture necessitates a specific form of interpretation, and the camera augments this physical experience. We perceive a strange realism in the way the camera is operated. It does not move randomly. It focuses and at times appears to be following something. It changes altitude and we have the sense that nothing is controlling it, neither human nor animal nor drone, but all of these things together. We imagine the ambiguous being behind the camera and for a moment we wonder if it might be some other form of intelligence. Repeatedly we ask about the reason for the shot in question – perhaps we should always ask this question in the case of all shots, images and films. The camera lingers on objects and situations and moves hither and thither, sometimes tracking objects, sometimes not. Shots repeat and yet seem different each time round. In the end, no doubt thanks to this method of filming and its quirky physical presentation, which is reminiscent of perceptual mechanisms of the brain that might be compared to hallucinations in which the image in the brain is compared with the image seen (as in the case of computers), we derive an unusually intense feeling of a real experience. Perhaps the artist wished to outsmart us and create reality from an image of reality. Oddly enough, it works.

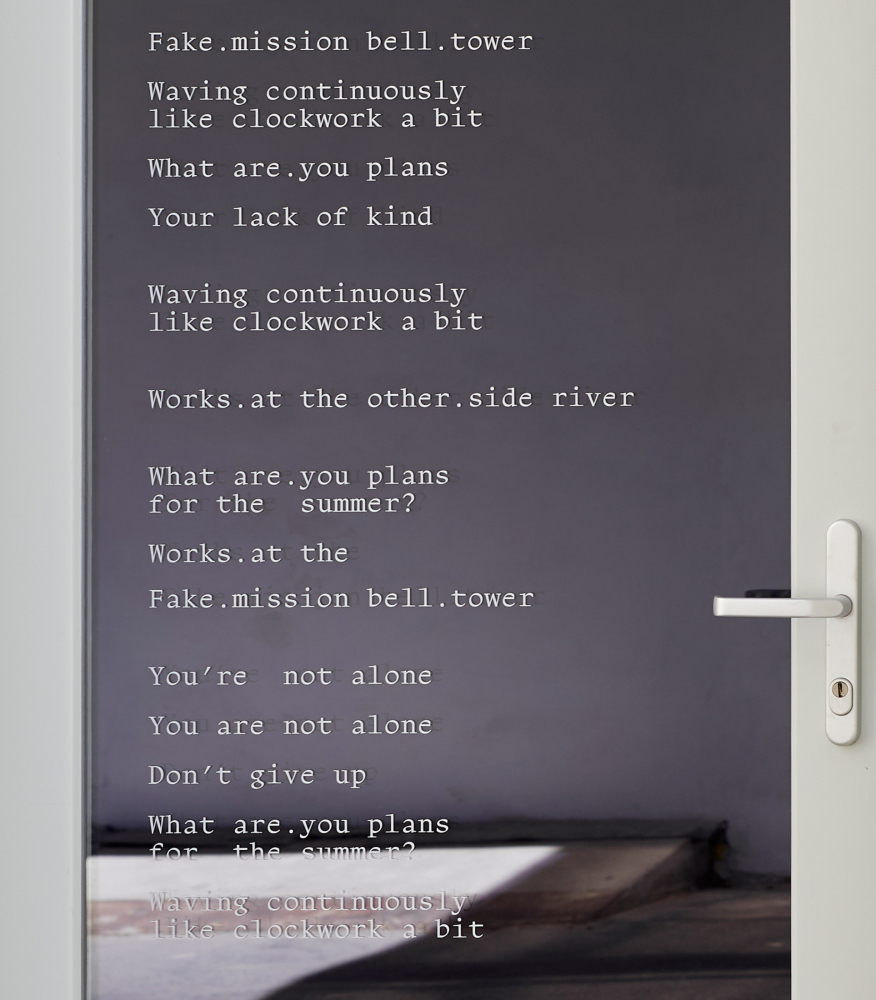

Well in advance of his exhibitions, Walwin studies carefully the physical qualities of the place it is to be held and its surroundings. He is interested in the relationship to a particular place and how his work enters it. He is also interested in the relationship of film and video to exhibitions in galleries and museums. On the lower of the suspended video monitors, the camera directs us through a kind of semi-automatic movement to read the text on shredded pieces of paper. These resemble the captions accompanying exhibits, and so for a moment we read them. Whoever enters the gallery will read on the door

True place (2019)

Center for Contemporary Arts Prague, curated by Edith Jeřábková

Mission place (2019)

HD video, 13 minutes, sound

Photographs by Filip Beránek

Graphic design by Filip Kraus

Sounds of Crisis, published by CCA Prague (2020), originally in Czech

1 Jiří Šubrt et al., Soudobá sociologie III (Diagnózy soudobých společností), Univerzita Karlova v Praze, Praha 2008, p. 271